2022 Federal Index

U.S. Department of Education

9

Leadership

Did the agency have senior staff members with the authority, staff, and budget to build and use evidence to inform the agency’s major policy and program decisions in FY22?

1.1 Did the agency have a senior leader with the budget and staff to serve as the agency’s Evaluation Officer or equivalent (example: Evidence Act 313)?

- The commissioner for the National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) serves as the Department of Education (ED) evaluation officer. The Institute of Education Sciences is primarily responsible for education research, evaluation, and statistics. It employed approximately 150 full-time staff in FY22. The NCEE commissioner is responsible for planning and overseeing ED’s major evaluations and oversees 23 staff members. The NCEE does not have a dedicated evaluation budget. Instead, funds for evaluation come from a combination of (1) evaluation set-asides created in programs’ authorizing legislation, (2) authority created in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act to reserve and/or pool appropriated funds for the purpose of evaluation, (3) national activities funds, and (4) individual appropriation bills.

1.2 Did the agency have a senior leader with the budget and staff to serve as the agency’s chief data officer or equivalent [example: Evidence Act 202(e)]?

- The Department of Education has a designated chief data officer. The Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development’s (OPEPD) Office of the Chief Data Officer (OCDO) has grown from a staff of twelve in FY20 to a staff of thirty-three full-time employees and detailees in FY22.

- The Evidence Act provides a framework for OCDO’s responsibilities, which include life cycle data management and developing and enforcing data governance policies. The OCDO has oversight over ED’s information collection approval and associated Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance process. It is responsible for developing and enforcing ED’s open data plan, including management of a centralized comprehensive data inventory accounting for all data assets across ED. The OCDO is also responsible for developing and maintaining a technological and analytical infrastructure that is responsive to ED’s strategic data needs, exploiting traditional and emerging analytical methods to improve decision-making, optimize outcomes, and create efficiencies. These activities are carried out by the Governance and Strategy Division, which focuses on data governance, life cycle data management, and open data and the Analytics and Support Division, which provides data analytics and infrastructure responsive to ED’s strategic data. The current OCDO budget reflects the importance of these activities to ED leadership, with salary and expense funding allocated for data governance, data analytics, open data, and information clearances.

1.3 Did the agency have a governance structure to coordinate the activities of its evaluation officer, chief data officer, statistical officer, performance improvement officer, and other related officials in order to support Evidence Act implementation and improve the agency’s major programs?

- The evaluation officer, chief data officer, and statistical officer meet monthly for the purposes of ensuring ongoing coordination of Evidence Act work. Each leader, or designee, also participates in the performance improvement officer’s Strategic Planning and Review process.

- The Evidence Leadership Group (ELG) supports program staff that run evidence-based grant competitions and monitor evidence-based grant projects. It advises ED leadership and staff on how evidence can be used to improve ED programs and provides support to staff in the use of evidence. It is co-chaired by the evaluation officer and the OPEPD director of grants policy. The statistical officer, evaluation officer, chief data officer, and performance improvement officer are ex-officio members of the ELG.

- The ED Data Governance Board (DGB) sponsors agency-wide actions to develop an open data culture and works to improve ED’s capacity to leverage data as a strategic asset for evidence building and operational decisions, including developing the capacity of data professionals in program offices. It is chaired by the chief data officer, with the statistical officer, evaluation officer, and performance improvement officer as ex officio members.

- The Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development advances the Secretary’s policy priorities including evidence, while IES is focused on (a) bringing extant evidence to policy conversations and (b) suggesting how evidence can be built as part of policy initiatives. It plays leading roles in the formation of ED’s policy positions as expressed through annual budget requests, grant competition priorities, including evidence. Both OPEPD and IES provide technical assistance to Congress to ensure that evidence appropriately informs policy design.

10

Evaluation & Research

Did the agency have an evaluation policy, evaluation plan, and learning agenda (evidence building plan), and did it publicly release the findings of all completed program evaluations in FY22?

2.1 Did the agency have an agency-wide evaluation policy [example: Evidence Act 313(d)]?

- The department’s evaluation policy is posted online at ed.gov/data. Key features of the policy include the department’s commitment to: (1) independence and objectivity, (2) relevance and utility, (3) rigor and quality, (4) transparency, and (5) ethics. Special features include additional guidance to ED staff on considerations for evidence building conducted by ED program participants, which emphasize the need for grantees to build evidence in a manner consistent with the parameters of their grants (e.g., purpose, scope, and funding levels) up to and including rigorous evaluations that meet IES’s What Works ClearinghouseTM (WWC) standards without reservations.

2.2 Did the agency have an agency-wide evaluation plan [example: Evidence Act 312(b)]?

- The Department’s FY23 Annual Evaluation Plan is posted at https://www.ed.gov/data under “Evidence-Building Deliverables,” as well as on evaluation.gov.

2.3 Did the agency have a learning agenda (evidence building plan) and did the learning agenda describe the agency’s process for engaging stakeholders including, but not limited to the general public, state and local governments, and researchers/academics in the development of that agenda (example: Evidence Act 312)?

- The Department’s FY22-FY26 Learning Agenda is posted at https://www.ed.gov/data under “Evidence-Building Deliverables,” as well as on evaluation.gov. The Learning Agenda describes both how stakeholders were engaged in the Agenda’s development, and how stakeholders are to be engaged after the Agenda’s publication.

2.4 Did the agency publicly release all completed program evaluations?

- The Institute of Education Sciences publicly releases all peer-reviewed publications from its evaluations on the IES website and also in the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). Many IES evaluations are also reviewed by its What Works Clearinghouse. The institute also maintains profiles of all evaluations on its website, both completed and ongoing, including key findings, publications, and products. It regularly conducts briefings on its evaluations for ED, the OMB, Congressional staff, and the public.

2.5 Did the agency conduct an Evidence Capacity Assessment that addressed the coverage, quality, methods, effectiveness, and independence of the agency’s evaluation, research, and analysis efforts [example: Evidence Act 3115, subchapter II (c)(3)(9]?

- The department’s FY22-FY26 Capacity Assessment is part of the agency’s FY22-FY26 Strategic Plan. It is also available at evaluation.gov.

2.6 Did the agency use rigorous evaluation methods, including random assignment studies, for research and evaluation purposes?

- The IES website includes a searchable database of planned and completed evaluations, including those that use experimental, quasi-experimental, or regression discontinuity designs. All impact evaluations rely upon experimental trials. Other methods, including matching and regression discontinuity designs, are classified as rigorous outcomes evaluations. The institute also publishes studies that are descriptive or correlational, including implementation studies and less rigorous outcome evaluations. The Department of Education’s evaluation policy outlines its commitment (p. 5) to leveraging a broad range of evaluation tools, including rigorous methods to best suit the needs of the research question.

5

Resources

Did the agency invest at least 1% of program funds in evaluations in FY22 (examples: Impact studies; implementation studies; rapid cycle evaluations; evaluation technical assistance, and rigorous evaluations, including random assignments)?

3.1 _____ invested $____ on evaluations, evaluation technical assistance, and evaluation capacity-building, representing __% of the agency’s $___ billion FY22 budget.

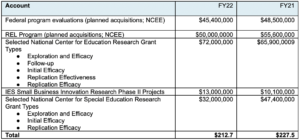

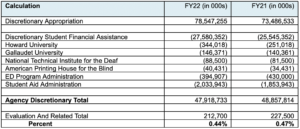

- The Department of Education invested $212,700,000 in high-quality evaluations of federal programs, evaluations as part of field-initiated research and development, technical assistance related to evaluation and evidence building, and capacity building in FY22. This includes work awarded by centers across the IES.

- This represents 0.44% of the agency’s $48,000,000,000 FY22 discretionary congressional appropriation, not including the accounts listed below.

3.2 Did the agency have a budget for evaluation and how much was it? (Were there any changes in this budget from the previous fiscal year?)

- The Department of Education does not have a specific budget solely for federal program evaluation. Evaluations are supported either by (a) required or allowable program funds or (b) ESEA Section 8601, which permits the Secretary to reserve up to 0.5% of selected ESEA program funds for rigorous evaluation. As part of the FY22 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress allowed the Secretary to reserve up to 0.5% of funds appropriated for programs authorized by the Higher Education Act for a range of evidence building activities. The department’s decision-making about the use of those funds is ongoing and is not represented below.

- The decrease in funds dedicated to federal program evaluations represents a combination of natural variation in resource needs across the life cycle of individual evaluations and the need to slow some activities in response to school closures associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.3 Did the agency provide financial and other resources to help city, county, and state governments or other grantees build their evaluation capacity (including technical assistance funds for data and evidence capacity building)?

- In June 2021, IES announced ALN 84.305S: Using Longitudinal Data to Support State Education Recovery Policymaking. As part of this program, IES supports state agencies’ use of their state’s education longitudinal data systems as they and local education agencies reengage their students after the disruptions caused by COVID-19. The maximum award is $1,000,000 over three years. Examples of recent (FY21 and FY22) grantees include state education agencies in Delaware, Massachusetts, Montana, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

- The Regional Education Laboratories provide extensive technical assistance on evaluation and support research partnerships that conduct implementation and impact studies on education policies and programs in ten geographic regions of theUnited States, covering all states, territories, and the District of Columbia.

- Comprehensive Centers provide support to states in planning and implementing interventions through coaching, peer-to-peer learning opportunities, and ongoing direct support. The State Implementation and Scaling Up of Evidence-Based Practices Center provides tools, training modules, and resources on implementation planning and monitoring.

8

Performance Management / Continuous Improvement

Did the agency implement a performance management system with outcome-focused goals and aligned program objectives and measures, and did it frequently collect, analyze, and use data and evidence to improve outcomes, return on investment, and other dimensions of performance in FY22?

4.1 Did the agency have a strategic plan with outcome goals, program objectives (if different), outcome measures, and program measures (if different)?

- Current (FY22-FY26) and past strategic plans, including the department’s goals, strategic objectives, implementation steps, and performance objectives can be found on the department’s website, which also contains department annual performance reports (most recent fiscal year) and annual performance plans (upcoming fiscal year) .

4.2 Does the agency use data/evidence to improve outcomes and return on investment?

- The Grants Policy Office within OPEPD works with offices across ED to ensure alignment with the Secretary’s priorities, including evidence-based practices. The Grants Policy Office looks at where ED and the field can continuously improve by building stronger evidence, making decisions based on a clear understanding of the available evidence, and disseminating evidence to decision-makers. Specific activities include strengthening the connection between the Secretary’s policies and grant implementation from design through evaluation; supporting a culture of evidence-based practices; providing guidance to grant-making offices on how to integrate evidence into program design; and identifying opportunities where ED and the field can improve by building, understanding, and using evidence. The Grants Policy Office collaborates with offices across the Department on a variety of activities, including reviews of efforts used to determine grantee performance.

- The Department of Education is focused on efforts to disaggregate outcomes by race and other demographics and to communicate those results to internal and external stakeholders. For example, in FY21, OCDO launched the Education Stabilization Fund (ESF) Transparency Portal at covid-relief-data.ed.gov, allowing ED to track performance, hold grantees accountable, and provide transparency to taxpayers and oversight bodies. The portal includes annual performance report data from CARES, Corona Virus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations, and ARP Act grantees, allowing ED and the public to monitor support for students and teachers and track the progress of the grantees. The portal displays key data from the annual performance reports, summarizing how the funds were used by states and districts. Data are disaggregated to the extent possible. For example, the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) form asks for counts of students who participated in various activities to support learning recovery or acceleration for subpopulations disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Categories include students with one or more disabilities, low-income students, English language learners, students in foster care, migratory students, students experiencing homelessness, and five race/ethnicity categories. As of July 2022, data in the portal includes information from the reporting period ending April 2022.

4.3 Did the agency have continuous improvement or learning cycle processes to identify promising practices, problem areas, possible causal factors, and opportunities for improvement (examples: stat meetings, data analytics, data visualization tools, or other tools that improve performance)?

- As part of the department’s performance improvement efforts, senior career and political leadership convene in quarterly performance review (QPR) meetings. As part of the QPR process, the performance improvement officer leads senior career and political officials in a review of ED’s progress toward its two-year agency priority goals and four-year strategic goals. In each QPR, assembled leadership reviews metrics that are “below target,” brainstorms potential solutions, and celebrates progress toward achieving goals that are “on track” for the current fiscal year.

- Since FY19, the department has conducted after-action reviews after each discretionary grant competition cycle to reflect on successes of the year as well as opportunities for improvement. The reviews resulted in process updates for FY21. In addition, the department updated an optional internal tool to inform policy deliberations and progress on the Secretary’s policy priorities, including the use of evidence and data.

8

Data

Did the agency collect, analyze, share, and use high-quality administrative and survey data-consistent with strong privacy protections – to improve (or help other entities improve) outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and/or the performance of federal, state, local, and other service providers programs in FY22 (examples:model data-sharing agreements or data-licensing agreements, data tagging and documentation, data standardization, open data policies, data use policies)

5.1 Did the agency have a strategic data plan, including an open data policy [example: Evidence Act 202(c), Strategic Information Resources Plan]?

- The ED Data Strategy–the first of its kind for the U.S. Department of Education–was released in December 2020. It recognized that we can, should, and will do more to improve student outcomes through the more strategic use of data. The ED Data Strategy goals are highly interdependent with cross-cutting objectives requiring a highly collaborative effort across ED’s principal offices. The strategy calls for strengthening data governance to administer the data the department uses for operations, answer important questions, and meet legal requirements. To accelerate evidence building and enhance operational performance, ED must make its data more interoperable and accessible for tasks ranging from routine reporting to advanced analytics. The high volume and evolving nature of ED’s data tasks necessitate a focus on developing a workforce with skills commensurate with a modern data culture in a digital age. At the same time, safely and securely providing access for researchers and policymakers helps foster innovation and evidence-based decision-making at the federal, state, and local levels.

- Goal 4 of the ED Data Strategy calls for ED to “improve data access, transparency, and privacy.” Objective 1.4 under this goal is to “develop and implement an open data plan that describes the department’s efforts to make its data open to the public.” Improving access to ED data, while maintaining quality and confidentiality, is key to expanding the agency’s ability to generate evidence to inform policy and program decisions. Increasing access to data for ED staff, federal, state, and local lawmakers, and researchers can help ED make new connections and foster evidence-based decision-making. Increasing access can also spur innovations that support ED’s stakeholders, provide transparency about ED’s activities, and serve the public good. The Department of Education seeks to improve user access by ensuring that open data assets are in a machine-readable open format and accessible via its comprehensive data inventory. The department will better leverage expertise in the field to expand its base of evidence by establishing a process for researchers to access non-public data. Further, ED will develop a cohesive and consistent approach to privacy and enhance information collection processes to ensure that department data are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable.

- The department continues to wait for Phase 2 guidance from OMB to understand the required parameters for the open data plan. In the meantime, ED continues to draft its open data plan. When finalized, the plan will conform to the new requirements associated with the release of OMB Phase 2 guidance. In the meantime, ED continues to release open data; the department soft-launched the Open Data Platform (ODP) in September 2020 and publicly released it in December 2020.

5.2 Did the agency have an updated comprehensive data inventory (example: Evidence Act 3511)?

- The ED Data Inventory (EDI) was developed in response to the requirements of M-13-13 and initially served ED’s external asset inventory. It describes data reported to ED as part of grant activities, along with administrative and statistical data assembled and maintained by ED. It includes descriptive information about each data collection along with information on the specific data elements in individual data collections.

- The ODP is the ED’s solution for publishing, finding, and accessing public data profiles. This open data catalog brings together the department’s data assets in a single location, making them available with their metadata, documentation, and APIs for use by the public. The ODP makes existing public data from all ED principal offices accessible to the public, researchers, and ED staff in one location. It improves the department’s ability to grow and operationalize its comprehensive data inventory while progressing on open data requirements. The Evidence Act requires government agencies to make data assets open and machine-readable by default. The Open Data Platform is ED’s comprehensive data inventory satisfying these requirements while also providing privacy and security. It features standard metadata contained in data profiles for each data asset. Before new assets are added, data stewards conduct quality review checks on the metadata to ensure accuracy and consistency. As the platform matures and expands, ED staff and the public will find it a powerful tool for accessing and analyzing ED data, either through the platform directly or through other tools powered by its API.

- Information about Department data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) has historically been made publicly available online. Prioritized data is further documented or featured on ED’s data page. NCES is also leading a government-wide effort to automatically populate metadata from Information Collection Request packages to data inventories. This may facilitate the process of populating EDI and comprehensive data inventory.

5.3 Did the agency promote data access or data linkage for evaluation, evidence-building, or program improvement?

- As ED collaboratively took stock of organizational data strengths and weaknesses, key themes arose and provided context for the development of the ED Data Strategy. The Strategy addresses new and emerging mandates such as open data by default, interagency data sharing, data standardization, and other principles found in the Evidence Act and Federal Data Strategy. However, improving strategic data management has benefits far beyond compliance; solving persistent data challenges and making progress against a baseline data maturity assessment offers ED the opportunity to close capability gaps and enable staff to make evidence-based decisions.

- One of the first priorities for the ED Data Governance Board (DGB) in FY21 was to assess the current state of data maturity at ED. In early 2020, OCDO held “discovery” meetings with stakeholders from each ED office to capture information about successes and challenges in the current data landscape. This activity yielded over 300 data challenges and 200 data successes that provided a wealth of information to inform future data governance priorities. The DGB used the understanding gained of the ED data landscape during the discovery phase to develop a Data Maturity Assessment (DMA) for each office and the overall enterprise focusing on data and related data infrastructure in line with requirements in the Federal Data Strategy 2020 Action Plan. Data maturity is a metric that will be measured and reported as part of ED’s Annual Performance Plan. Several of these activities have been supported by ED’s investment in a Data Governance Board and Data Governance Infrastructure (DGBDGI) contract.

- ED has also made concerted efforts to improve the availability and use of its data with the release of the revised College Scorecard that links data from NCES, the Office of Federal Student Aid, and the Internal Revenue Service. Through a series of recent updates, the College Scorecard team has improved the functionality of the tool to allow users to find, compare, and contrast different fields of study more easily, access expanded data on the typical earnings of graduates two years post-graduation, view median parent PLUS loan debt at specific institutions, and learn about the typical amount of federal loan debt for students who transfer. OCDO facilitated reconsideration of IRS risk assumptions to enhance data coverage and utility while still protecting privacy. The Scorecard enhancement discloses for prospective students how well borrowers from institutions are meeting their federal student loan repayment obligations, as well as how borrower cohorts are faring at certain intervals in the repayment process.

- IES continues to make available all data collected as part of its administrative data collections, sample surveys, and evaluation work. Its support of the Common Education Data Standards (CEDS) Initiative has helped to develop a common vocabulary, data model, and tool set for P-20 education data. The CEDS Open Source Community is active, providing a way for users to contribute to the standards development process.

5.4 Did the agency have policies and procedures to secure data and protect personal, confidential information (example: differential privacy; secure, multiparty computation; homomorphic encryption; or developing audit trails)?

- The Student Privacy Policy Office (SPPO) leads the U.S. Department of Education’s (Department) efforts to protect privacy. SPPO manages and maintains the Department’s privacy program to include the enforcement of student privacy laws, and in addition, serves at the epicenter of the Department’s privacy program, ensuring compliance with applicable privacy requirements, developing and evaluating privacy policy, and managing privacy risks across the Department. Through its role as the Department’s leader in privacy policy, implementation, education, and training, SPPO raises awareness of privacy issues, demonstrates how Departmental personnel can safeguard personally identifiable information (PII), and fosters a culture of accountability for protecting PII within the Department. These efforts are implemented through the work of SPPO’s Privacy Safeguards Team, including the Disclosure Review Board (DRB), and is supported by its Privacy Technical Assistance Center.

5.5 Did the agency provide assistance to city, county, and/or state governments, and/or other grantees on accessing the agency’s datasets while protecting privacy?

- The Department’s Data Review Board (DRB), assists Principal Offices in managing privacy risks before releasing data assets to the public. The DRB reviews data assets prior to public release to evaluate and manage the risk of unauthorized disclosure of PII, as well as to minimize unnecessary privacy risks with any authorized disclosure of PII. In addition, the DRB establishes best practices and provides technical assistance for applying privacy and confidentiality protections in the context of the public release of data assets.

- SPPO’s Privacy Technical Assistance Center (PTAC) established by the Department as a technical assistance resource center for education stakeholders to learn about privacy requirements and related best practices for student data systems. In this capacity, PTAC responds to technical assistance inquiries on student privacy issues and provides online FERPA training to state and school district officials. FSA conducted a postsecondary institution breach response assessment to determine the extent of a potential breach and provide the institutions with remediation actions around their protection of FSA data and best practices associated with cybersecurity.

- The Institute of Education Sciences (IES) administers a restricted-use data licensing program to make detailed data available to researchers when needed for in-depth analysis and modeling. NCES loans restricted-use data only to qualified organizations in the United States. Individual researchers must apply through an organization (e.g., a university, a research institution, or company). To qualify, an organization must provide a justification for access to the restricted-use data, submit the required legal documents, agree to keep the data safe from unauthorized disclosures at all times, and to participate fully in unannounced, unscheduled inspections of the researcher’s office to ensure compliance with the terms of the License and the Security Plan form.

- The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) provides free online training on using its data tools to analyze data while protecting privacy. Distance Learning Dataset Training includes modules on NCES’s data-protective analysis tools, including QuickStats, PowerStats, and TrendStats. A full list of NCES data tools is available on their website.

10

Common Evidence Standards / What Works Designations

Did the agency use a common evidence framework, guidelines, or standards to inform its research and funding purposes; did that framework prioritize rigorous research and evaluation methods; and did the agency disseminate and promote the use of evidence-based interventions through a user friendly tool in FY22 (example: What Works Clearinghouses)?

6.1 Did the agency have a common evidence framework for research and evaluation purposes?

- ED has an agency-wide framework for impact evaluations that is based on ratings of studies’ internal validity. ED evidence-building activities are designed to meet the highest standards of internal validity (typically randomized control trials) when causality must be established for policy development or program evaluation purposes. When random assignment is not feasible, rigorous quasi-experiments are conducted. The framework was developed and is maintained by IES’s What Works Clearinghouse (WWC). Standards are maintained on the WWC website. A stylized representation of the standards can be found here, along with information about how ED reports findings from research and evaluations that meet these standards.

- Since 2002, ED—as part of its compliance with the Information Quality Act and OMB guidance—has required that all “research and evaluation information products documenting cause and effect relationships or evidence of effectiveness should meet quality standards that will be developed as part of the What Works Clearinghouse” (see Information Quality Guidelines).

6.2 Did the agency have a common evidence framework for funding decisions?

- The Department of Education employs the same evidence standards in all discretionary grant competitions that use evidence to direct funds to applicants proposing to implement projects that have evidence of effectiveness and/or to build new evidence through evaluation. Those standards, as outlined in the Education Department General Administrative Regulations (EDGAR), build on ED’s WWC research design standards.

6.3 Did the agency have a clearinghouse(s) or user-friendly tool that disseminated information on rigorously evaluated, evidence-based solutions (programs, interventions, practices, etc.) including information on what works where, for whom, and under what conditions?

- ED’s What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) identifies studies that provide valid and statistically significant evidence of effectiveness of a given practice, product, program, or policy (referred to as “interventions”), and disseminates summary information and reports on the WWC website.

- The WWC has published more than 611 Intervention Reports, which synthesize evidence from multiple studies about the efficacy of specific products, programs, and policies. Wherever possible, Intervention Reports also identify key characteristics of the analytic sample used in the study or studies on which the Reports are based.

- The WWC has published nearly 30 Practice Guides, which synthesize across products, programs, and policies to surface generalizable practices that can transform classroom practice and improve student outcomes.

- Finally, the WWC has completed nearly 12,000 single study reviews. Each is available in a searchable database.

6.4 Did the agency promote the utilization of evidence-based practices in the field to encourage implementation, replication, and application of evaluation findings and other evidence?

- ED has several technical assistance programs designed to promote the use of evidence-based practices, most notably IES’s Regional Educational Laboratory Program and the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education’s Comprehensive Center Program. Both programs use research on evidence-based practices generated by the What Works Clearinghouse and other ED-funded Research and Development Centers to inform their work. RELs also conduct applied research and offer research-focused training, coaching, and technical support on behalf of their state and local stakeholders. Their work is reflected in the Department’s Strategic Plan.

- Often, those practices are highlighted in WWC Practice Guides, which are based on syntheses (most recent meta-analyses) of existing research and augmented by the experience of practitioners. These guides are designed to address challenges in classrooms and schools.

- To ensure continuous improvement of the kind of TA work undertaken by the RELs and Comprehensive Centers, ED has invested in both independent evaluation and grant-funded research. Additionally, IES has awarded two grants to study and promote knowledge utilization in education, including the Center for Research Use in Education and the National Center for Research in Policy and Practice. In June of 2020, IES released a report on How States and Districts Support Evidence Use in School Improvement, which may be of value to technical assistance providers and SEA and LEA staff in improving the adoption and implementation of evidence-based practice.

- Finally, the ED developed revised evidence definitions and related selection criteria for competitive programs that align with ESSA to streamline and clarify provisions for grantees. These revised definitions align with ED’s suggested criteria for states’ implementation of ESSA’s four evidence levels, included in ED’s non-regulatory guidance, Using Evidence to Strengthen Education Investments. ED also developed a fact sheet to support internal and external stakeholders in understanding the revised evidence definitions. This document has been shared with internal and external stakeholders through multiple methods, including the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education ESSA technical assistance page for grantees.

6

Innovation

Did the agency have staff, policies, and processes in place that encouraged innovation to improve the impact of its programs in FY22? (Examples: Prizes and challenges; behavioral science trials; innovation labs/accelerators; performance partnership pilots; demonstration projects or waivers with rigorous evaluation requirements)

7.1 Did the agency have staff dedicated to leading its innovation efforts to improve the impact of its programs?

- The Innovation and Engagement Team in the Office of the Chief Data Officer promotes data integration and sharing, making data accessible, understandable, and reusable; engages the public and private sectors on how to improve access to the Department’s data assets; develops solutions that provide tiered access based on public need and privacy protocols; develops consumer information portals and products that meet the needs of external consumers; and partners with OCIO and ED data stewards to identify and evaluate new technology solutions for improving collection, access, and use of data. This team led the ED work on the ESF transparency portal, highlighted above, and also manages and updates College Scorecard. The team is currently developing ED’s first Open Data Plan and a playbook for data quality at ED.

7.2 Did the agency have initiatives to promote innovation to improve the impact of its programs?

- The Education Innovation and Research (EIR) program is ED’s primary innovation program for K-12 public education. EIR grants are focused on validating and scaling evidence-based practices and encouraging innovative approaches to persistent challenges. The EIR program incorporates a tiered-evidence framework that supports larger awards for projects with the strongest evidence base as well as promising earlier-stage projects that are willing to undergo rigorous evaluation. Lessons learned from the EIR program have been shared across the agency and have informed policy approaches in other programs.

7.3 Did the agency evaluate its innovation efforts, including using rigorous methods?

- ED’s Experimental Sites Initiative is entirely focused on assessing the effects of statutory and regulatory flexibility in one of its most critical programs: Title IV Federal Student Aid programs. FSA collects performance and other data from all participating institutions, while IES conducts rigorous evaluations–including randomized trials–of selected experiments. Recent examples include ongoing work on Federal Work Study and Loan Counseling, as well as recently published studies on short-term Pell grants.

- The Education Innovation and Research (EIR) program, ED’s primary innovation program for K-12 public education, incorporates a tiered-evidence framework that supports larger awards for projects with the strongest evidence base as well as promising earlier-stage projects that are willing to undergo rigorous evaluation.

15

Use of Evidence in Competitive Grant Programs

Did the agency use evidence of effectiveness when allocating funds from its competitive grant programs in FY22? (Examples: Tiered-evidence frameworks; evidence-based funding set-asides; priority preference points or other preference scoring for evidence; Pay for Success provisions)

8.1 What were the agency’s five largest competitive programs and their appropriations amount (and were city, county, and/or state governments eligible to receive funds from these programs)?

- ED’s top five program accounts based on actual appropriation amounts in FY22 are:

- TRIO ($1.1 billion; eligible applicants: eligible grantees: institutions of higher education, public and private organizations);

- Charter Schools Program ($440 million; eligible grantees: varies by program, including state entities, charter management organizations, public and private entities, and local charter schools)

- GEAR UP ($378 million; eligible grantees: state agencies; partnerships that include IHEs and LEAs)

- Comprehensive Literacy Development Grants ($192 million; eligible grantees: state education agencies).

- Teacher and School Leader Incentive Program (TSL) ($173 million; eligible grantees: local education agencies, partnerships between state and local education agencies; and partnerships between nonprofit organizations and local educational agencies);

8.2 Did the agency use evidence of effectiveness to allocate funds in its five largest competitive grant programs? (e.g., Were evidence-based interventions/practices required or suggested? Was evidence a significant requirement?)

- ED uses evidence of effectiveness when making awards in its largest competitive grant programs.

- Each of the FY 2022 competitions for new awards under the Upward Bound, Upward Bound Math and Science, Veterans Upward Bound, and McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program T included a competitive preference priority for projects that proposed strategies supported by evidence that demonstrates a rationale. These competitions provide points for applicants that propose a project with a key component in its logic model that is informed by research or evaluation findings that suggest it is likely to improve relevant outcomes. FY 2022 funding also supported continuation awards to grantees that were successful in prior competitions that encouraged applicants to provide evidence that demonstrates a rationale (through competitive preference priorities in the FY 2021 Talent Search and Educational Opportunity Centers competitions and through a selection factor in the FY 2020 Student Support Services competition).

- Under the Charter Schools Program–and in several others agency-wide–ED generally requires or encourages applicants to support their project through logic models as well as other requirements and selection criteria to support the use of evidence-based practices and demonstrate effectiveness. In the FY22 competitions for Developers (Grants for the Opening of New Charter Schools – ALN 84.282B and Grants for the Replication and Expansion of High-Quality Charter Schools – ALN 84.282E) and for State Entities (ALN 84.282A), the Department included a selection criteria to provide points to applicants based on the extent to which the project demonstrates a rationale, meaning that a key project component included in the project’s logic model is informed by research or evaluation findings that suggest the project component is likely to improve relevant outcomes. In the Developer competitions, the Department required all applicants to provide a logic model and within the Replication and Expansion program (84.282E), ED also included a selection criteria related to the quality of the applicant and the extent to which they have a prior track record of success. A portion of the FY22 funding for the CSP was also used to fund additional unfunded applicants from the FY21 Credit Enhancement competition, which provided points to applicants based on the extent to which the project focused on assisting charter schools with a likelihood of success and the greatest demonstrated need for assistance under the program. Finally, a portion of FY22 funds were also dedicated to continuation awards to grantees who competed successfully in prior competitions, including those for the 2020 Charter Management Organization cohort, which also required a logic model and evidence of a track record of success

- The Department used a portion of the FY 2022 funding for new awards to high-scoring unfunded applicants from the FY 2021 competitions, which included competitive preference priorities for strategies based on moderate evidence (State competition) and Promising evidence (Partnership competition). In addition, the majority of FY 2022 funding supported continuation awards to States and Partnerships that competed successfully in previous competitions, including the FY 2021 competitions, the FY 2019 State competition (which included a competitive preference priority for strategies based on Promising evidence), the FY 2018 competitions (which included a selection factor for strategies that demonstrate a rationale), and the FY 2017 competitions (which included a CPP for strategies based on moderate evidence of effectiveness).

- The TSL statute requires applicants to provide a description of the rationale for their project and describe how the proposed activities are evidence-based, and grantees are held to these standards in the implementation of the program.

- The Comprehensive Literacy Development (CLD) statute requires that grantees provide subgrants to local educational agencies that conduct evidence-based literacy interventions. ESSA requires ED to give priority to applicants that meet the higher evidence levels of strong or moderate evidence, and in cases where there may not be significant evidence-based literacy strategies or interventions available, for example in early childhood education, encourage applicants to demonstrate a rationale.

8.3 Did the agency use its five largest competitive grant programs to build evidence? (e.g., requiring grantees to participate in evaluations)

- The Evidence Leadership Group (ELG) advises program offices on ways to incorporate evidence in grant programs through encouraging or requiring applicants to propose projects that are based on research and by encouraging applicants to design evaluations for their proposed projects that would build new evidence.

- ED’s grant programs require some form of an evaluation report on a yearly basis to build evidence, demonstrate performance improvement, and account for the utilization of funds. For examples, please see the annual performance reports of TRIO, the Charter Schools Program, and GEAR UP. The Teacher and School Leader Incentive Program is required by ESSA to conduct a national evaluation. The Comprehensive Literacy Development Grant requires evaluation reports. In addition, IES is currently conducting rigorous evaluations to identify successful practices in TRIO-Educational Opportunities Centers and GEAR UP. In FY19, IES released a rigorous evaluation of practices embedded within TRIO-Upward Bound that examined the impact of enhanced college advising practices on students’ pathway to college.

8.4 Did the agency use evidence of effectiveness to allocate funds in any other competitive grant programs (besides its five largest grant programs)?

- The Education Innovation and Research (EIR) program supports the creation, development, implementation, replication, and taking to scale of entrepreneurial, evidence-based, field-initiated innovations designed to improve student achievement and attainment for high-need students. The program uses three evidence tiers to allocate funds based on evidence of effectiveness, with larger awards given to applicants who can demonstrate stronger levels of prior evidence and produce stronger evidence of effectiveness through a rigorous, independent evaluation. The FY21 competition included checklists, a webinar, and PowerPoints to help applicants clearly understand the evidence requirements.

- ED incorporates the evidence standards established in EDGAR as priorities and selection criteria in many competitive grant programs. In addition, the Secretary’s Supplemental Priorities that can be used in the Department’s grant programs advance areas supported by evidence, and include evidence-based approaches in various ways.

8.5 What are the agency’s 1-2 strongest examples of how competitive grant recipients achieved better outcomes and/or built knowledge of what works or what does not?

- The EIR program supports the creation, development, implementation, replication, and scaling up of evidence-based, field-initiated innovations designed to improve student achievement and attainment for high-need students. IES released The Investing in Innovation Fund: Summary of 67 Evaluations, which can be used to inform efforts to move to more effective practices. An update to that report, capturing more recent grants, is currently being developed. ED continues to explore the results of these studies, and other feedback received from grantees and the public, to determine how lessons from EIR can strengthen both that and other ED programs.

8.6 Did the agency provide guidance which makes clear that city, county, and state government, and/or other grantees can or should use the funds they receive from these programs to conduct program evaluations and/or to strengthen their evaluation capacity-building efforts?

- In 2016, ED released non-regulatory guidance to provide state educational agencies, local educational agencies (LEAs), schools, educators, and partner organizations with information to assist them in selecting and using “evidence-based” activities, strategies, and interventions, as defined by ESSA, including carrying out evaluations to “examine and reflect” on how interventions are working. However, the guidance does not specify that federal competitive funds can be used to conduct such evaluations. Frequently, though, programs do include a requirement to evaluate the grant during and after the project period.

7

Use of Evidence in Non-Competitive Grant Programs

Did the agency use evidence of effectiveness when allocating funds from its non-competitive grant programs in FY22? (Examples: Evidence-based funding set-asides; requirements to invest funds in evidence-based activities; Pay for Success provisions)

9.1 What were the agency’s five largest non-competitive programs and their appropriation amounts (and were city, county, and/or state governments eligible to receive funds from these programs)?

- ED’s largest non-competitive programs based on actual appropriation amounts in FY22 are:

- Title I Grants to LEAs ($17.5 billion; eligible grantees: state education agencies);

- IDEA Grants to States ($14.2 billion; eligible grantees: state education agencies);

- Supporting Effective Instruction State Grants ($2.2 billion; eligible grantees: state education agencies);

- Impact Aid Payments to Federally Connected Children ($1.5 billion; eligible grantees: local education agencies);

- 21st Century Community Learning Centers ($1.3 billion; eligible grantees: state education agencies).

9.2 Did the agency use evidence of effectiveness to allocate funds in the largest five non-competitive grant programs? (e.g., Are evidence-based interventions/practices required or suggested? Is evidence a significant requirement?)

- Section 1003 of ESSA requires states to set aside at least 7% of their Title I, Part A funds for a range of activities to help school districts improve low-performing schools. School districts and individual schools are required to create action plans that include “evidence-based” interventions that demonstrate strong, moderate, or promising levels of evidence.

9.3 Did the agency use its five largest non-competitive grant programs to build evidence? (e.g., requiring grantees to participate in evaluations)

- ESEA requires a National Assessment of Title I– Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged. In addition, Title I Grants require state education agencies to report on school performance, including those schools identified for comprehensive or targeted support and improvement.

- Federal law (ESEA) requires states receiving funds from 21st Century Community Learning Centers to “evaluate the effectiveness of programs and activities” that are carried out with federal funds (section 4203(a)(14)), and it requires local recipients of those funds to conduct periodic evaluations in conjunction with the state evaluation (section 4205(b)).

- The Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP), the implementing office for IDEA grants to states, implements an accountability system that puts more emphasis on results through the use of Results Driven Accountability.

9.4 Did the agency use evidence of effectiveness to allocate funds in any other non-competitive grant programs (besides its five largest grant programs)?

- Section 4108 of ESEA authorizes school districts to invest “safe and healthy students” funds in Pay for Success initiatives. Section 1424 of ESEA authorizes school districts to invest their Title I, Part D funds (Prevention and Intervention Programs for Children and Youth Who are Neglected, Delinquent, or At-Risk) in Pay for Success initiatives; under the section 1415 of the same program, a State agency may use funds for Pay for Success initiatives.

9.5 What are the agency’s 1-2 strongest examples of how non-competitive grant recipients achieved better outcomes and/or built knowledge of what works or what does not?

- States and school districts are implementing the requirements in Title I of the ESEA regarding using evidence-based interventions in school improvement plans. Some States are providing training or practice guides to help schools and districts identify evidence-based practices.

9.6 Did the agency provide guidance which makes clear that city, county, and state government, and/or other grantees can or should use the funds they receive from these programs to conduct program evaluations and/or to strengthen their evaluation capacity-building efforts?

- In 2016, ED released non-regulatory guidance to provide state educational agencies, local educational agencies (LEAs), schools, educators, and partner organizations with information to assist them in selecting and using “evidence-based” activities, strategies, and interventions, as defined by ESSA, including carrying out evaluations to “examine and reflect” on how interventions are working. However, the guidance does not specify that federal non-competitive funds can be used to conduct such evaluations.

5

Repurpose for Results

In FY22, did the agency shift funds away from or within any practice, policy, or program that consistently failed to achieve desired outcomes? (Examples: Requiring low-performing grantees to re-compete for funding; removing ineffective interventions from allowable use of grant funds; incentivizing or urging grant applicants to stop using ineffective practices in funding announcements; proposing the elimination of ineffective programs through annual budget requests; incentivizing well-designed trials to fill specific knowledge gaps; supporting low-performing grantees through mentoring, improvement plans, and other forms of assistance; using rigorous evaluation results to shift funds away from a program)

10.1 Did the agency have policy(ies) for determining when to shift funds away from grantees, practices, policies, interventions, and/or programs that consistently failed to achieve desired outcomes, and did the agency act on that policy?

- The Department works with grantees to support the implementation of their projects to achieve intended outcomes. The Education Department General Administrative Regulations (EDGAR) explains that ED considers whether grantees make “substantial progress” when deciding whether to continue grant awards. In deciding whether a grantee has made substantial progress, ED considers information about grantee performance. If a continuation award is reduced, more funding may be made available for other applicants, grantees, or activities. Under some grant programs, due to statutory requirements or historical practices, programs assess performance from the three first years of grant activities to determine whether to provide two additional years of funding as part of a five-year grant.

10.2 Did the agency identify and provide support to agency programs or grantees that failed to achieve desired outcomes

- The Department conducts a variety of technical assistance to support grantees to improve outcomes. Department staff work with grantees to assess their progress and, when needed, provide technical assistance to support program improvement. On a national scale, the Comprehensive Centers program, Regional Educational Laboratories, and technical assistance centers managed by the Office of Special Education Programs develop resources and provide technical assistance. The Department uses a tiered approach in these efforts, providing universal general technical assistance through a more general dissemination strategy; targeted technical assistance efforts that address common needs and issues among a number of grantees, and intensive technical assistance that is more focused on specific issues faced by specific recipients. The Department also supports program-specific technical assistance for a variety of individual grant programs.